Here you can find some hints, comments and tables that can be useful while learning Russian from zero.

\

\

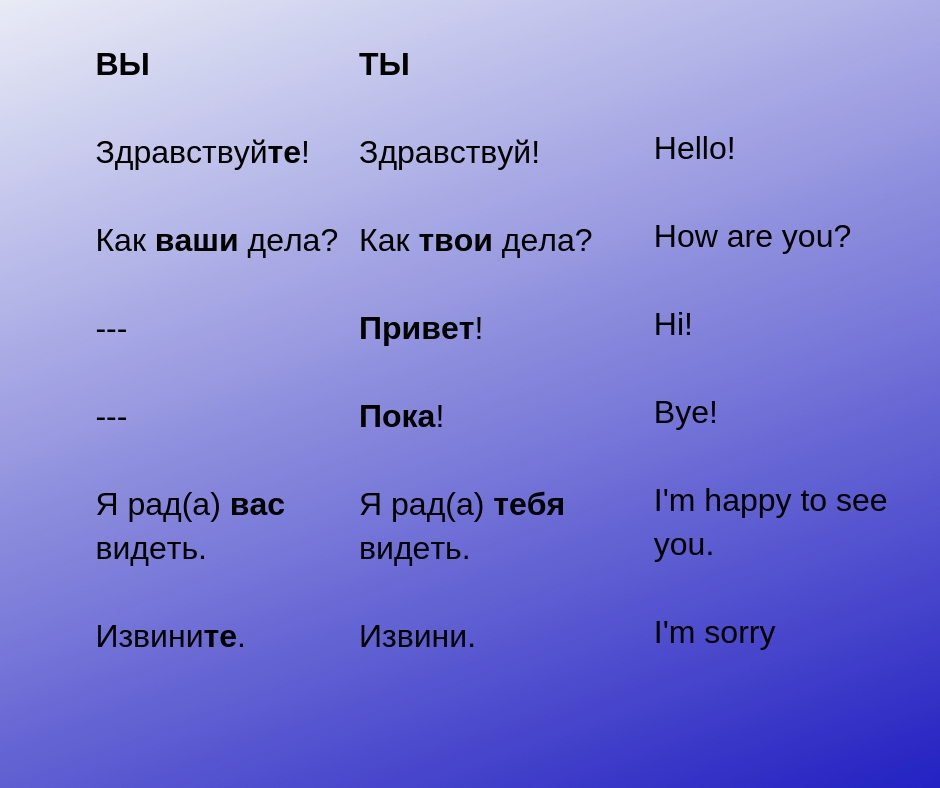

ТЫ and ВЫ

\

There’re 2 way of address in Russian:

ТЫ (informal)

ВЫ (formal).

Some other languages also have 2 or even more forms of address. But how do we use it?

The way to use “ты” and “вы” in Russian is quite close to French “tu” and “vous” and is dramatically different from Spanish “tu” and “usted”, for example.

The most popular form of address in Russian is “вы” – formal!

We use it in the majority of situations – talking to people in a street, in a store, in metro… We address “вы” to any person we’re not acquainted with or we’ve got acquainted with recently.

“Ты” works for kids, members of your family and close friends.

Be careful with the forms of address! If you use “ты” inappropriately, Russians would treat you like an impolite, rude, bad-behavior person. If you’re not sure, it’s always safer to say “вы”.

Check the table and pay attention to the way you address to people in Russian.

\

\

\

A BANK IS “HE”, A PHARMACY IS “SHE”, AN EMBASSY IS “IT” – WHAT IS IT ABOUT???

\

– Вот ОН, справа.

(Tell me please, where’s a bank near here? – IT’s on your right).

– А где здесь аптека?

– Вот ОНА, слева.

(And where is a pharmacy near here? – IT’s on your left).

\

– А где здесь посольство Индии?

– ОНО там.

(And where’s the embassy of India? – IT’s overthere).

\

Let’s resume.

In English “bank”, “pharmacy”, “embassy” are “it”, and it’s logical.

In Russian:

“банк” (bank) is “он” (he)

“аптека” (pharmacy) is “она” (she)

“посольство” (embassy) is “оно” (it),

and it seems like there’s no logic in it. What’s that?

Yes, there’s no logic here if we think about the meanings of these words.

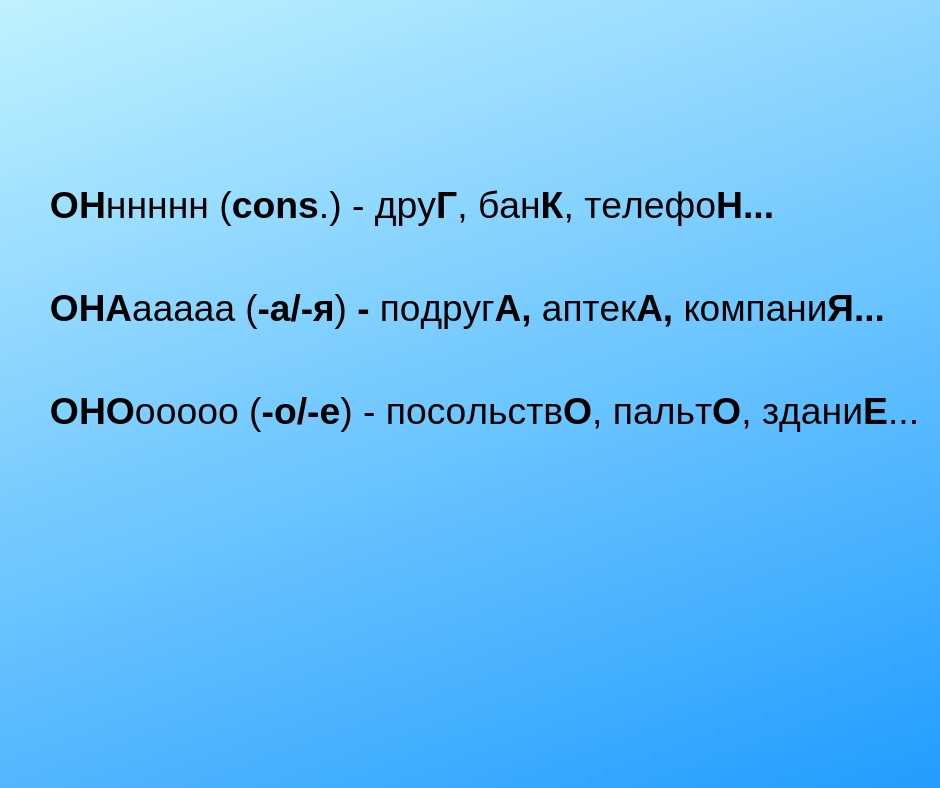

It’s a feature of the Russian grammar. Any noun in Russian has its GRAMMATICAL gender, and the pronouns ОН (he), ОНА (she) and ОНО (it) refer to this grammatical gender and not to the lexical meaning.

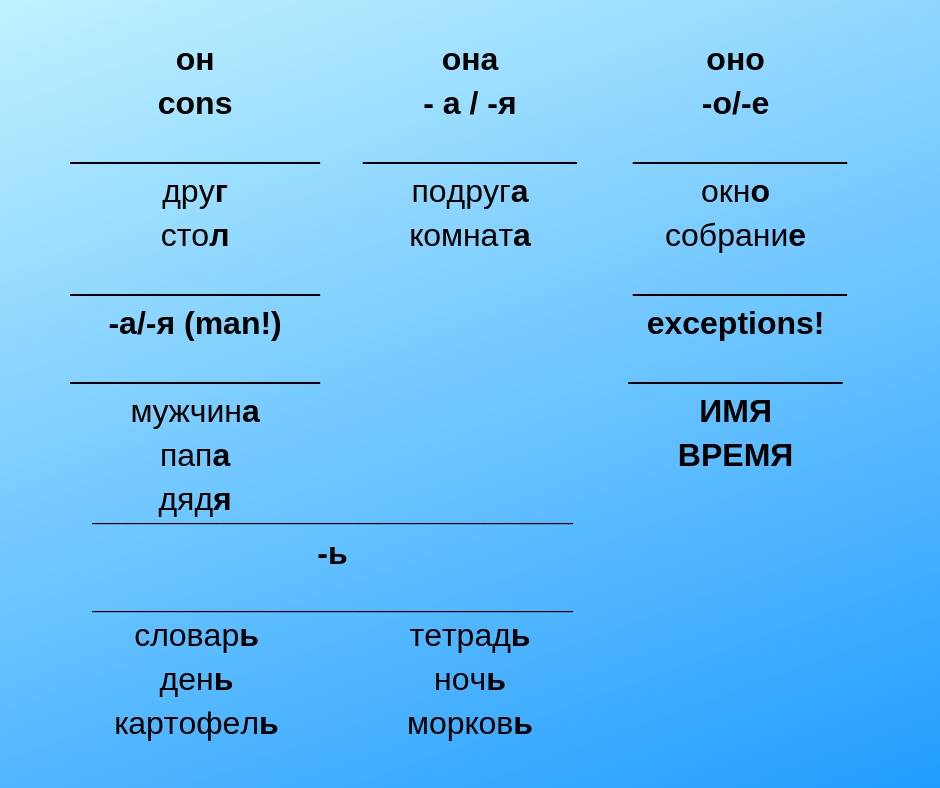

Check the table below to learn how to define the gender of a noun in Russian.

\

The hint is the words ОН (he), ОНА (she), ОНО (it).

How does it work?

\

The word ОН ends in a consonant- and all the words that end in a consonant are “он” (masculine): друГ, банК, телефоН etc.

\

The word ОНА ends in “-а” – and the words that end in “-а” or -я” are “она” (feminine): подругА, аптекА, компаниЯ etc.

\

The word ОНО ends in “-о” – and the words that end in “-о” or “-е” are “онo” (neuter): посольствО, пальтО, зданиЕ etc. (there’s “о / е” correspondence in the Russian grammar).

\

This is the basic rule to define a gender of a noun in Russian. And you need just to refer to the ОН, ОНА, ОНО words to apply it.

The next feature is that some words have “-а” or -я” in the end but they are masculine.

Don’t be afraid! You don’t need to memorize anything! A word with “-а” or -я” in the end is masculine, ONLY if it’s absolutely clear from its meaning: мужчина (man), папа (father), дядя (uncle) etc.

\

The last part of the rule is the worst one. If a word ends in the soft sign, it can be either masculine or feminine 50%-50% to remember. Any time you meet a new word with “-ь” in the end, you have to check in a dictionary if its ОН or ОНА and memorize it. In this case the grammar gender has nothing to do with the meaning and the examples from the table demonstrate it.

\

\

\

ЭТО ВАШ КОШЕЛЁК?

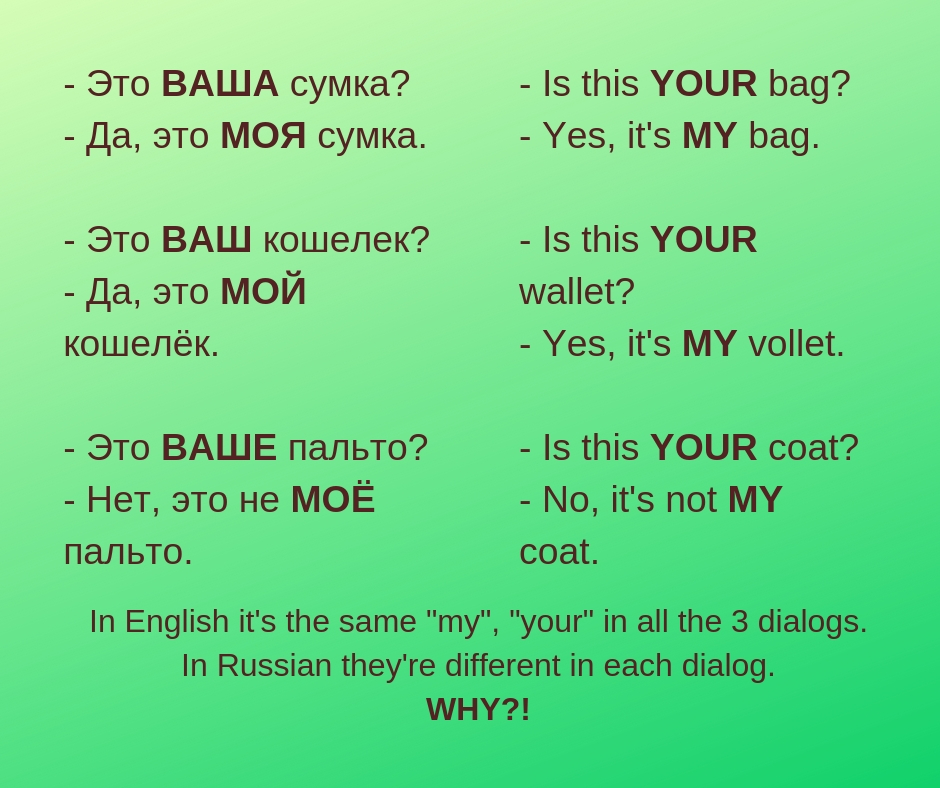

- Это ВАША сумка?

– Да, это МОЯ сумка.

(Is this YOUR bag? – Yes, it’s MY bag.)

\

- Это ВАШ кошелек?

– Да, это МОЙ кошелёк.

(Is this YOUR wallet? – Yes, it’s MY vollet.)

- Это ВАШЕ пальто?

– Нет, это не МОЁ пальто.

(Is this YOUR coat? – No, it’s not MY coat.)

\

Let’s resume.

\

In English:

bag, wallet, coat – MY, YOUR (same for all the nouns)

\

In Russian:

сумка (bag) – МОЯ, ВАША

кошелёк (wallet) – МОЙ, ВАШ

пальто (coat) – МОЁ, ВАШЕ

The forms of the words “мой” (my), “ваш” (your) are different in each case.

\

What do you think, why are they different and what does it depend on?

\

\

Thus, here is one more reason why we need to indentify a gender of a noun – it’s because a form of a possessive pronoun (мой, твой, наш, ваш, чей) depends on it.

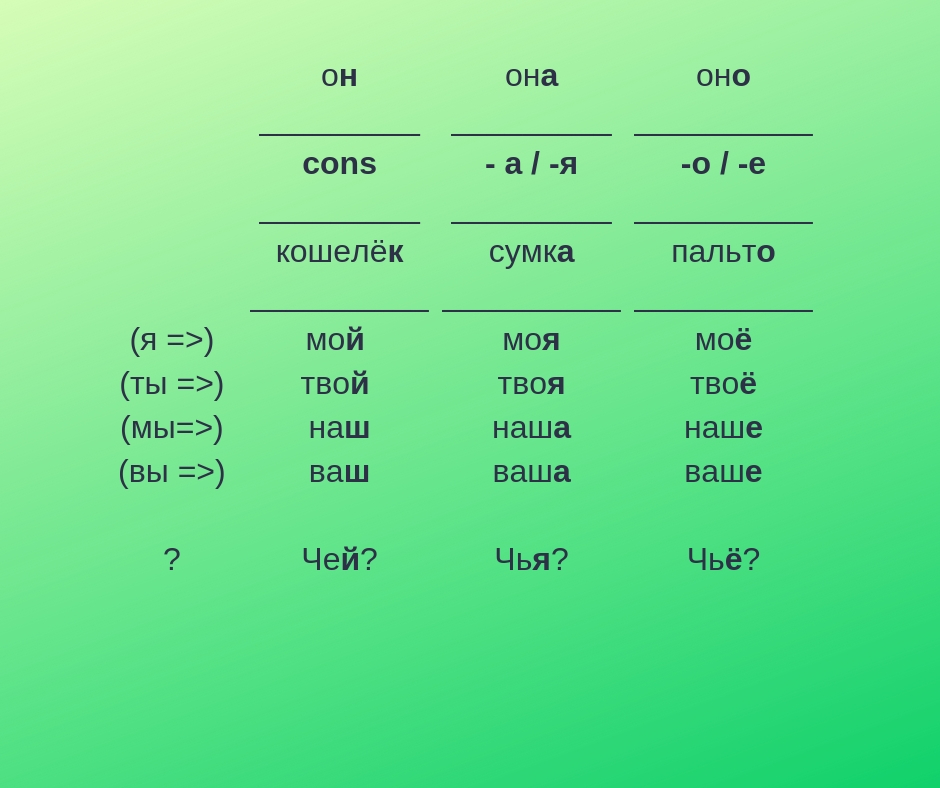

Look at the table below to check the masculine, feminine and neuter forms of the words МОЙ, ТВОЙ, НАШ, ВАШ, ЧЕЙ.

\

Pay attention that the system remains absolutely logical.

\

Consonats work for ОН – моЙ, твоЙ, наШ, ваШ, чеЙ (if you can’t recognize “й” as a consonant, check one of my previous posts about this sound).

\

“-а / -я” work for ОНА – моЯ, твоЯ, нашА, вашА, чьЯ.

\

“-о / -е” work for ОНО – моЁ, твоЁ (phonetically [майО], [твайО]), нашЕ, вашЕ, чьЁ [чйО].

\

You can check some excersises to practice ОН-ОНА-ОНО, МОЙ-МОЯ-МОЁ etc. here: http://ohrussian.com/2018/08 , http://ohrussian.com/2018/09, http://ohrussian.com/2018/10

\

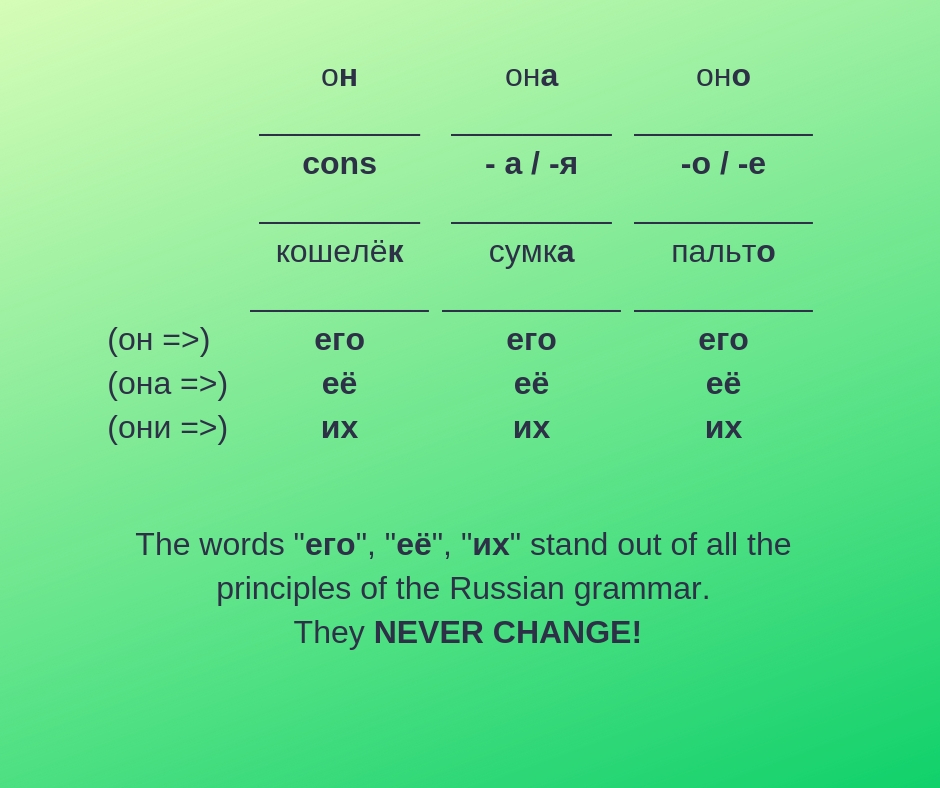

ЭТО ЕГО КОШЕЛЁК??

\

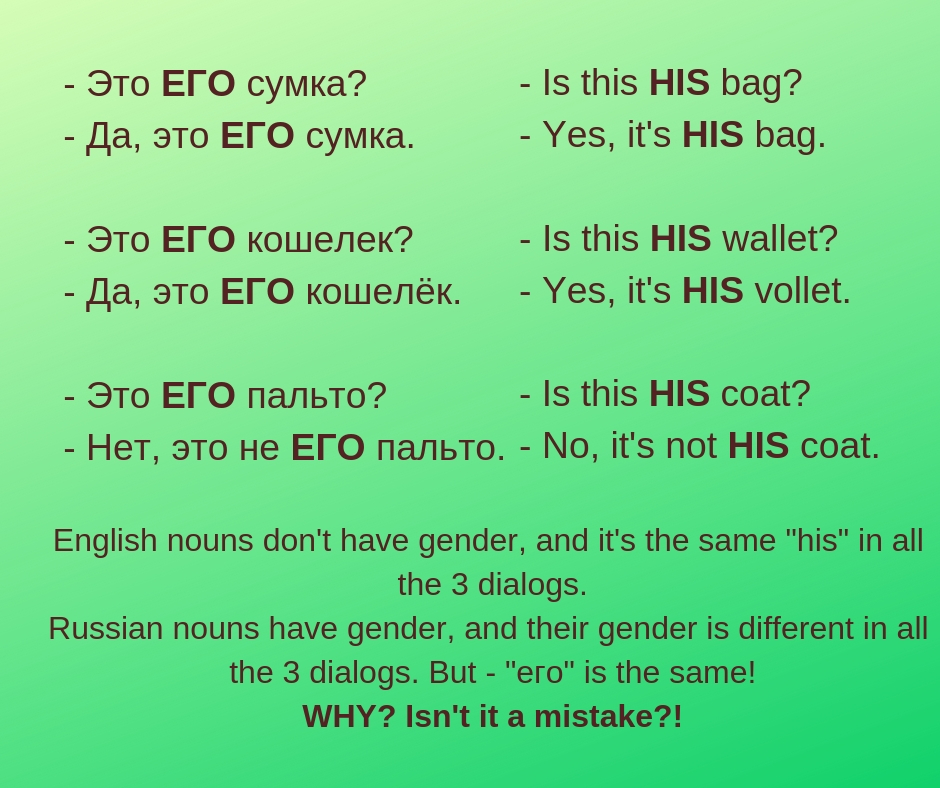

- Это ЕГО сумка?

– Да, это ЕГО сумка.

(Is this HIS bag? – Yes, it’s HIS bag.)

\

- Это ЕГО кошелек?

– Да, это ЕГО кошелёк.

(Is this HIS wallet? – Yes, it’s HIS vollet.)

– Это ЕГО пальто?

– Нет, это не ЕГО пальто.

(Is this HIS coat? – No, it’s not HIS coat.)

\

Let’s resume.

\

In English:

bag, wallet, coat – HIS (same for all the nouns)

\

In Russian:

сумка, кошелёк, пальто – ЕГО (same for all the nouns)

\

But we have already learned that in Russian

сумка (bag) – она, feminine

кошелёк (wallet) – он, masculine

пальто (coat) – оно, neuter

and we used different forms of the words “мой”, “ваш” for each of them. We know that this form does depend on a gender.

\

And now – ЕГО – just the same ЕГО – goes with “кошелёк”, “сумка” and “пальто”. What’s going on? Is there a mistake??? Does a form of a possessive pronoun depend on a gender of a noun or does it not?!

\

The feature is that there’re 3 special words in Russian:

ЕГО (his)

ЕЁ (her)

ИХ (their).

These words NEVER CHANGE.

NEVER-EVER!!!

\

They stand out of all the principles of the Russian grammar. They don’t have different gender forms, the don’t have singular/plural forms, they don’t have forms for different cases.

\

ЕГО, ЕЁ, ИХ are always ЕГО, ЕЁ, ИХ – and that’s it!!!

\

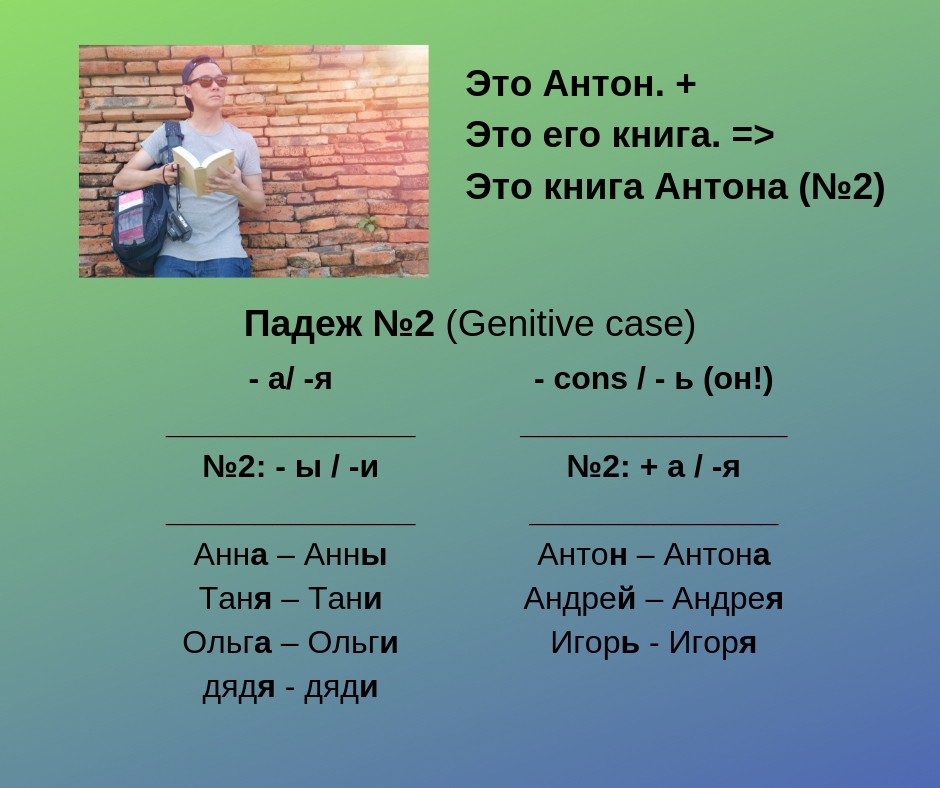

ЭТО АНТОН, А ЭТО ЕГО КНИГА.

ЧЬЯ ЭТО КНИГА?

\

Это Антон.

(This is Anton.)

\

Это его книга.

(This is his book.)

\

How can we combine these 2 ideas in 1 sentence to say “This is Anton’s book”?

\

\

Падеж №2 (Genitive)

Это Антон. +

Это его книга. =>

Это книга Антона (№2).

\

We have to modify the word “Антон” and say it in the form of Genitive case (form №2) without a preposition.

Attention:

the word order is strict here! It’s like “a book OF Anton”. We can’t replace the words “книга” and “Антон” in this model.

\

\

\

This rule isn’t so difficult. But let’s pay attention to some points.

\

1. How do you understand, does the ending of падеж №2 depend on a gender of a noun?

\

2. The first column of the table explains, that if the last letter is “-а” or “-я”, we have to replace it with “-ы ” or “-и” to get to the падеж №2 form. Which words will have “-ы ” and which words will have “-и”, – what’s the criterium?

\

3. The second column of the table explains, that if the last letter is a consonant or “-ь” masculine, the endings for падеж №2 are “+а” or “-я”. I. e. if it’s a consonant, we ADD “а” (Антон + а = Антона: книга Антона), and if the last letter is “-ь”, we REPLACE it with “-я” (Игорь – Игоря: книга Игоря). What’s about the last letter “-й”? We know that “й” is a consonant! How does it work then?

\

And here are the answers.

\

1. Does the ending of падеж №2 depend on a gender of a noun?

\

– If the last letter is “-а” or “-я”, an ending NEVER depends on a gender of noun. Feminine and masculine nouns have the same endings: Оля – книга Оли (№2), дядя – книга дяди (№2).

\

– If the last letter is “-ь”, an ending ALWAYS depends on a gender. Macsuline and feminine nouns with “-ь” have 100% different grammar endings!

2. If the last letter is “-а” or “-я”, we have to replace it with “-ы ” or “-и” to get to the падеж №2 form. Which words have “-ы ” and which words have “-и”, – what’s the criterium?

\

– Normally “-а” becomes “-ы” and “-я” becomes “-и”. But there’re specials consonants in Russian that NEVER can be used with “ы”. These consonants are:

К, Г, Х

Ч, Щ

Ж, Ш.

\

If any grammar rule leads us to a combination of one of these letters with “ы”, we should use “и” instead:

кы => КИ

гы => ГИ

хы => ХИ

чы => ЧИ

щы => ЩИ

жы => ЖИ (in spelling, but [жы] in pronunciation)

шы => ШИ (in spelling, but [шы] in pronunciation)

\

That’s why Ольга becomes Ольги ( книга Ольги (№2)) with “и” and not “ы” in the end.

\

3. If the last letter is a consonant or “-ь” masculine, the endings for падеж №2 are “+а” or “-я”. I. e. if it’s a consonant, we ADD “а” (Антон + а = Антона: книга Антона), and if the last letter is “-ь”, we REPLACE it with “-я” (Игорь – Игоря: книга Игоря). What’s about the last letter “-й”? We know that “й” is a consonant! How does it work then?

\

– Last letter “-й” works the same as any other consonant: we add “а” to it.

Андрей+а=Андре[йа]. The only feature is that we never spell “йа” – we spell one letter “я” instead: книга Андрея (№2).

\

КТО ЭТО? vs. КТО ОН?

\

What is the difference between the questions “Кто это?” and “Кто он?”

How can you answer each of these questions?

\

\

\

The question “Кто это?” is very wide and doesn’t require any special information about a person. Everything works here:

\

– Кто это?

– Это Игорь.

\

or

\

– Кто это?

– Это мой друг.

\

or

\

– Кто это?

– Это преподаватель.

\

So, possible dialogs are:

\

– Кто он?

– Он преподаватель.

\

or

\

– Кто он?

– Он бизнесмен.

\

or

\

– Кто он?

– Он студент.

\

or

\

– Кто он?

– Он пенсионер.

\

But answers like “Игорь”, “Антон Борисович”, “мой друг”, “мой брат” and others that have nothing to do with education, profession, occupation or social status don’t work for “Кто он?” question.

\

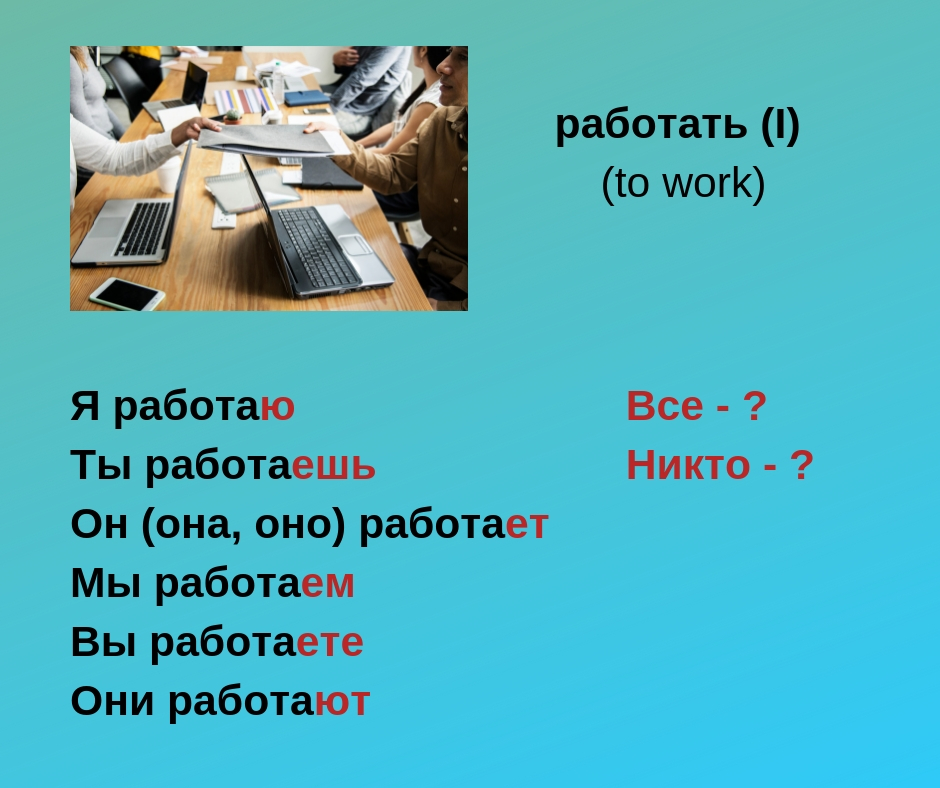

Verbs (group I)

Present tense

Я работаю в LG.

(I work for LG).

\

A classical example of group I verbs is the verb “работать” (to work):

\

Я работаю

Ты работаешь

Он (она, оно) работает

Мы работаем

Вы работаете

Они работают.

\

What do you think, what forms of a verb should be used for “все” (everybody) and “никто” (nobody)?

\

“Все” (“everybody”) in Russian is “они”:

Они работаЮТ =>

=> Все работаЮТ.

\

“Кто” (“who”), “никто” (“nobody”) in Russian is “он”:

Он работаЕТ =>

=> Кто работаЕТ?

\

We always use DOUBLE NEGATION in Russian:

Никто НЕ работаЕТ.

\

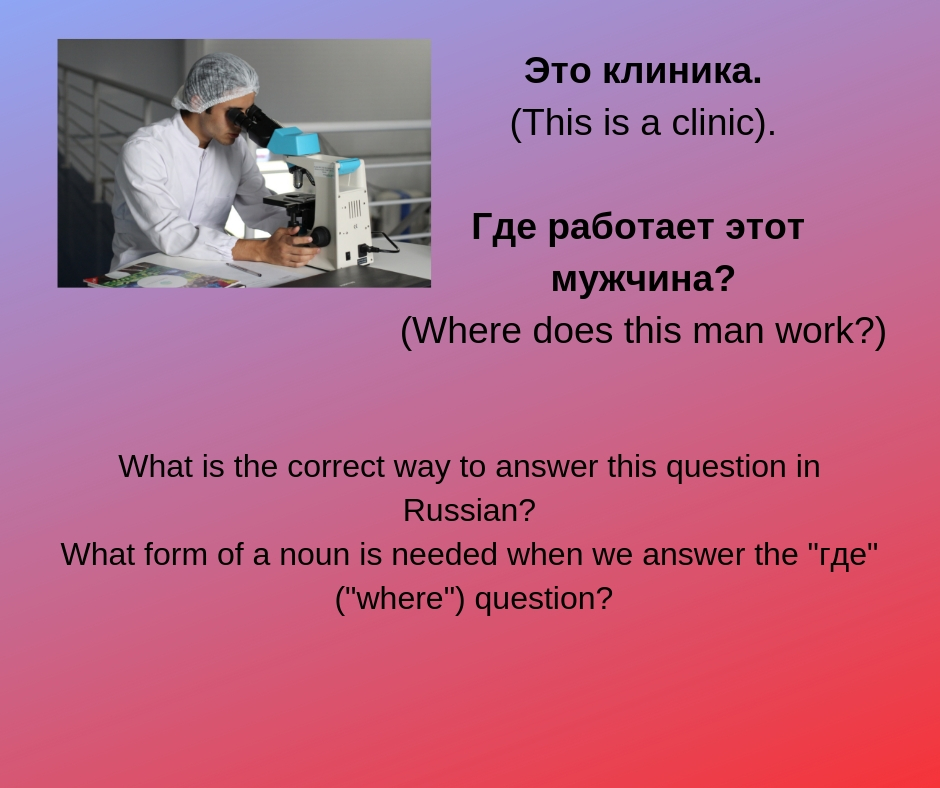

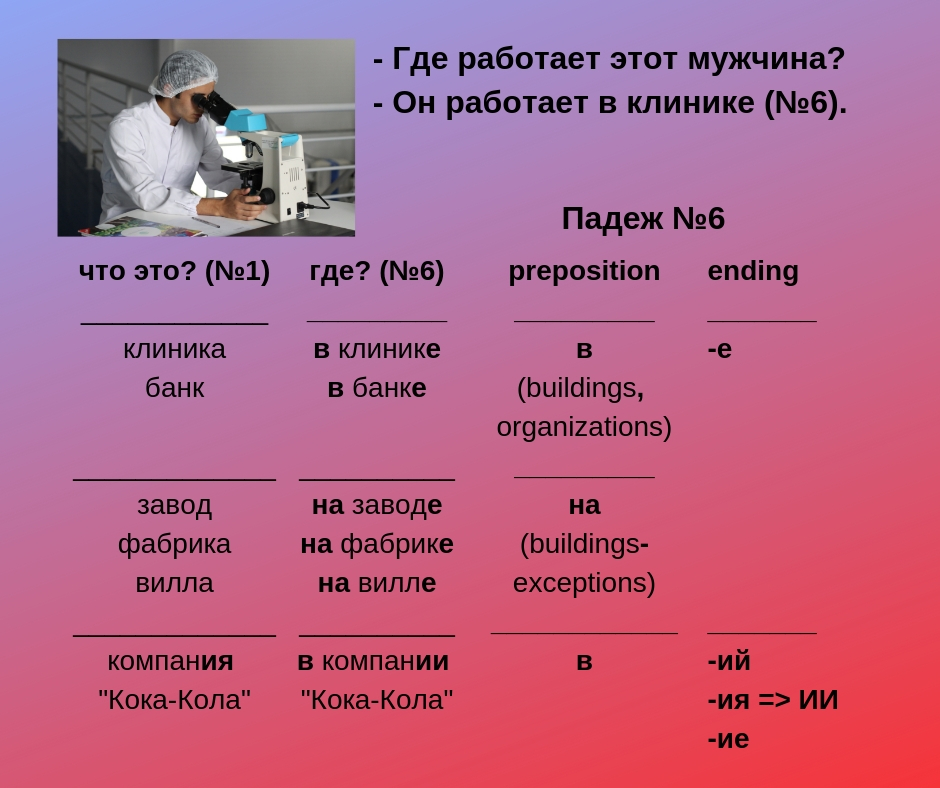

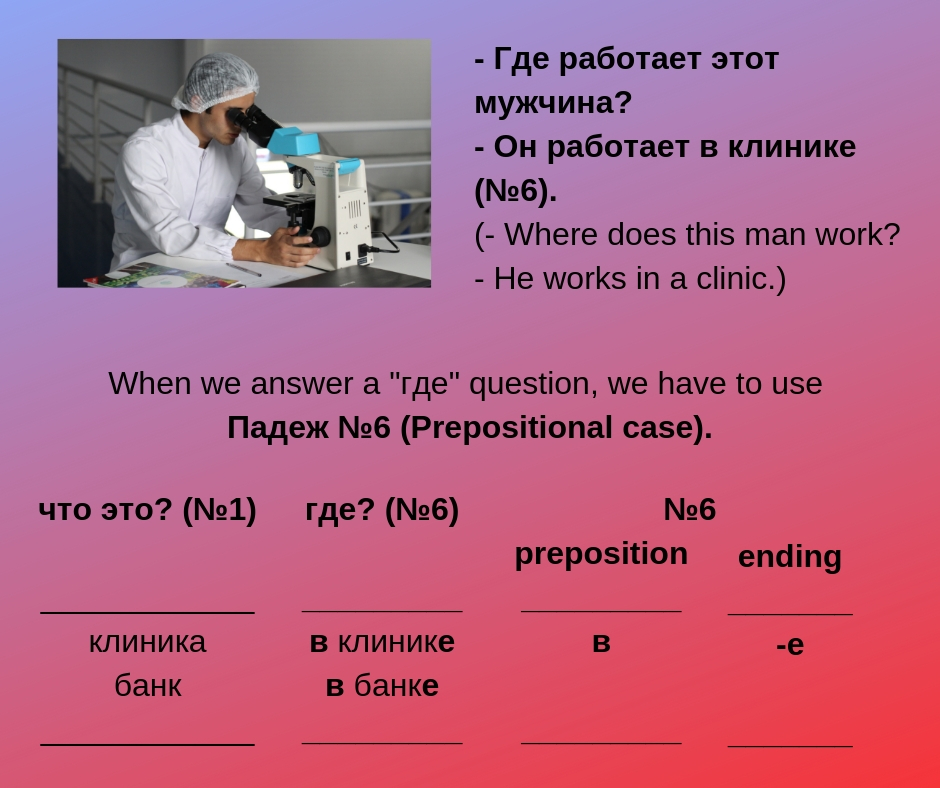

Где работает этот мужчина?

\

What is the correct way to answer this question in Russian?

What form of a noun is needed when we answer the “где” (“where”) question?

\

Падеж №6 (Prepositional)

– ГДЕ работает этот мужчина?

– Он работает В КЛИНИКЕ (№6).

(- Where does this man works?

– He works in a clinic).

\

When we answer a “где?” question, we have to use Prepositional case (падеж №6).

\

This form consists of 2 parts – a preposition and an ending.

\

Pay attention: this form is called “Prepositional” – it’s never used without a preposition!

\

The prepositions that are used here are “В” (more or less close to English “in”) or “НА” (more or less close to English “on”, “at”).

\

The most typical ending is “-е”. You can memorize it easity – just listen to the question:

– Гдееееее?

\

\

\В and НА

The basic difference between “В” and “НА” prepositions is that

“В” means inside of smth

“НА” means on a surface of smth.

Sometimes this criterion is enough to understand what preposition is to be used for the Prepositional case form in a particular situation.

\

Sometimes the criterion mentioned above is enough to understand what preposition is to be used – В or НА.

But sometimes it’s not that evident and additional criteria are needed.

For example when we’re talking about place of work the nouns that we use are buildings or organizations.

\

If it’s a building or organization, the preposition is В.

\

And there’re some exceptions. The exceptions (buildings/ organizations used with НА preposition) are:

\

завод – (работать) НА заводе

фабрика – (работать) НА фабрике

почта – (работать) НА почте

вилла – (работать) НА вилле.

\

The basic ending for Prepositional case is “-Е”.

\

Another ending used there is “-И”.

A noun has “-И” instead of “-Е” in the Prepositional case form, if in a dictionary form it ends in “-ИЙ”, “-ИЯ” or “-ИЕ”.

\

For example:

\

компанИЯ “Кока-Кола” – (работать) в компанИИ “Кока-Кола”.

\

\

It’s really hard to learn any grammar form if you try to memorize a rule only. It’s looking so abstract that it’s almost about nothing.

\

When you learn a grammar form, it’s necesary to memorize speech examples.

\

Here I offer you an audio with phrases that contain nouns in Prepositional case (№6) vs. Nominative case (№1). Listening to this audio will help you to memorize Prepositional case form of nouns singular.

\

The phrases in the audio are:

\

Это клиника (№1). Он работает в клинике (№6).

(This is a clinic. He works in a clinic).

\

Это больница (№1). Он работает в больнице (№6).

(This is a hospital. He works in a hospital).

\

Это банк (№1). Он работает в банке (№6).

(This is a bank. He works in a bank).

\

Это ресторан (№1). Она работает в ресторане (№6).

(This is a restaurant. She works in a restaurant).

\

Это завод (№1). Он работает на заводе (№6).

(This is a factory (car factory). He works in a factory).

\

Это фабрика (№1). Она работает на фабрике (№6).

(This is a factory (clothing factory). She works in a factory).

\

Это компания (№1) Samsung. Он работает в компании (№6) Samsung.

(This is a Samsung company. He works for a Samsung company).

\

Это компания (№1) LG. Он работает в компании (№6) LG.

(This is an LG company. She works for an LG company).

\

\

\

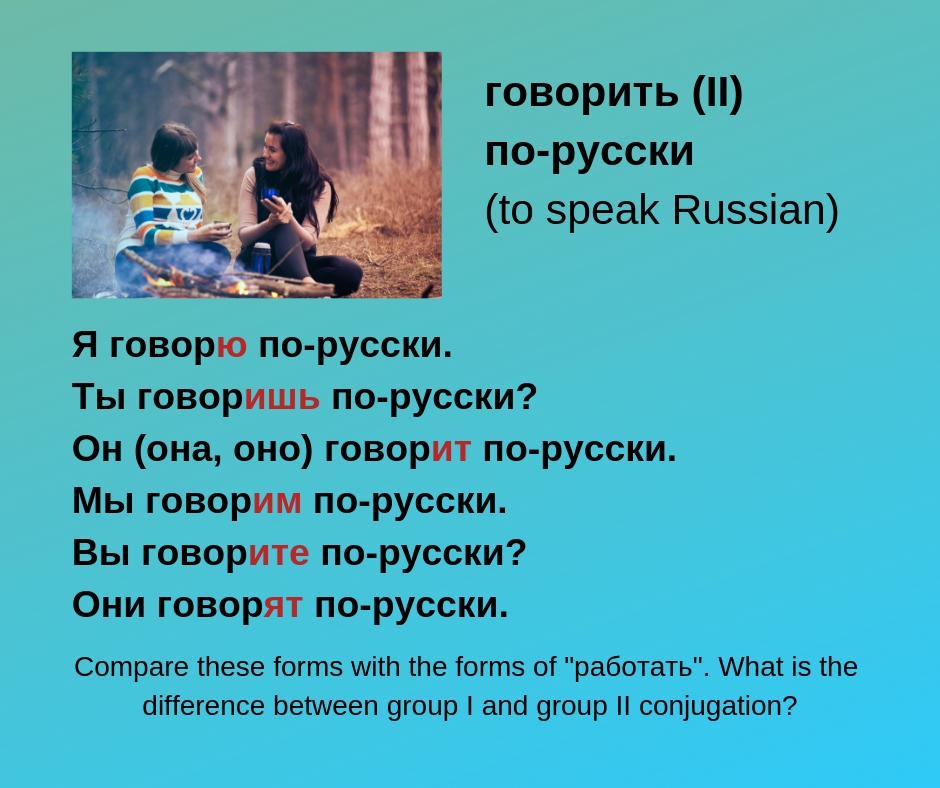

Verbs (group II)

Present tense

A classical example of group II verbs is the verb “говорить” (to speak) – for example, “говорить по-русски” (to speak Russian):

Я говорю по-русски.

Ты говоришь по-русски?

Он (она, оно) говорит по-русски.

Мы говорим по-русски.

Вы говорите по-русски?

Они говорят по-русски.

\

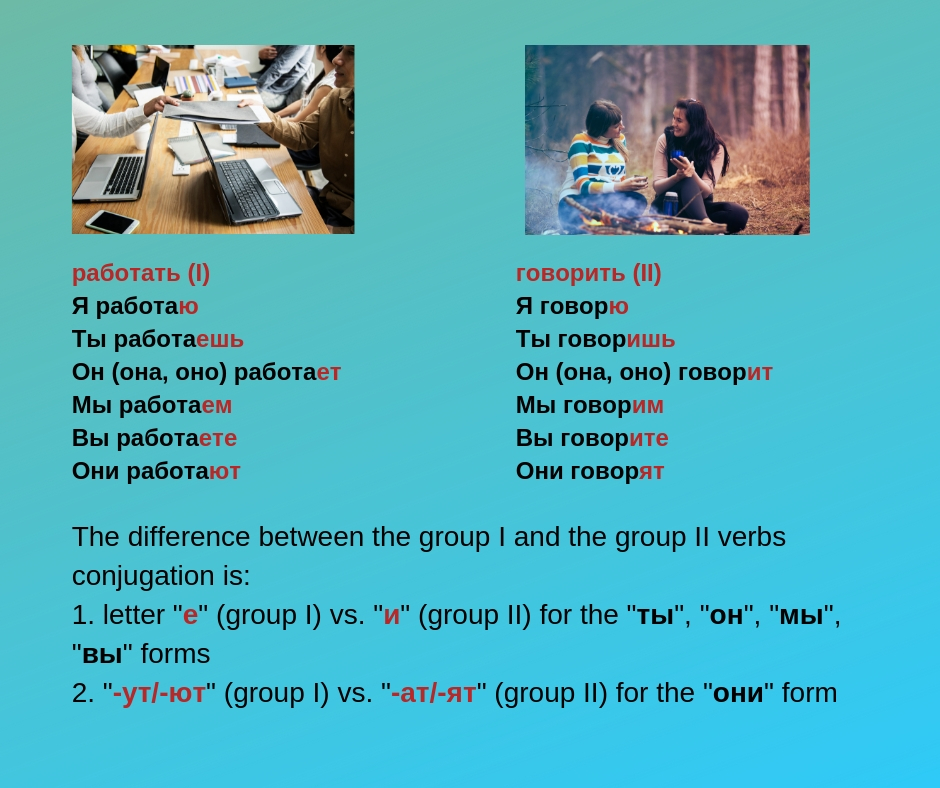

Look at these forms and compare them with the forms of “работать”. What is the difference between group I and group II conjugation?

\

\

The difference between the group I and the group II verbs conjugation is:

\

1. letter “е” (group I) vs. “и” (group II) for the “ты”, “он”, “мы”, “вы” forms

2. “-ут/-ют” (group I) vs. “-ат/-ят” (group II) for the “они” form

\

\

\

\

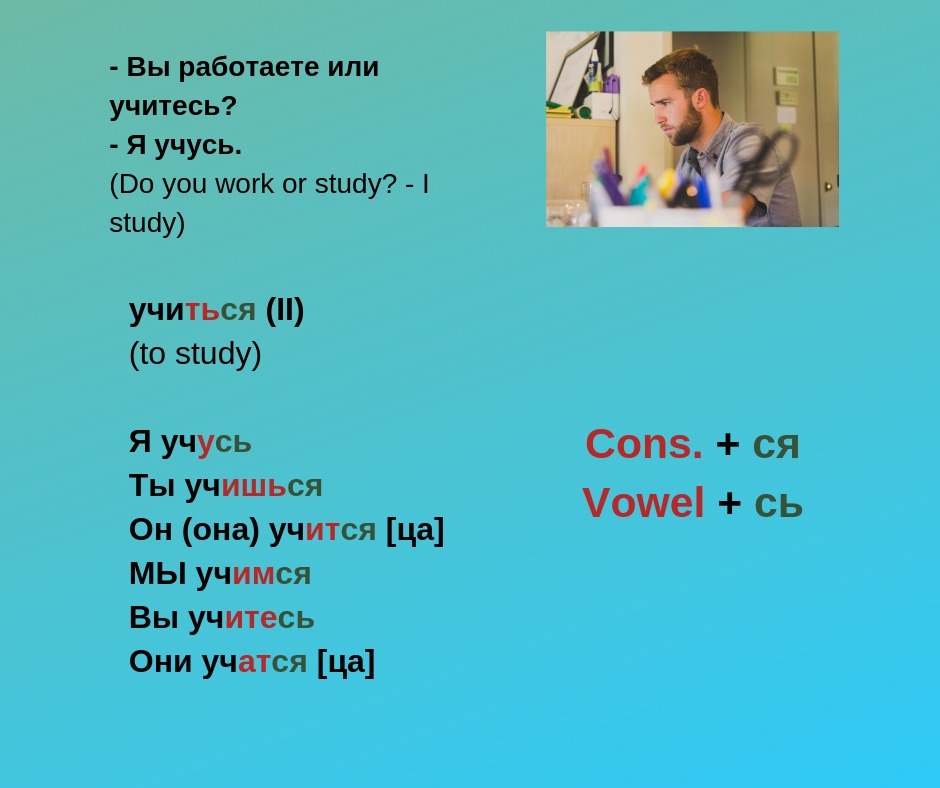

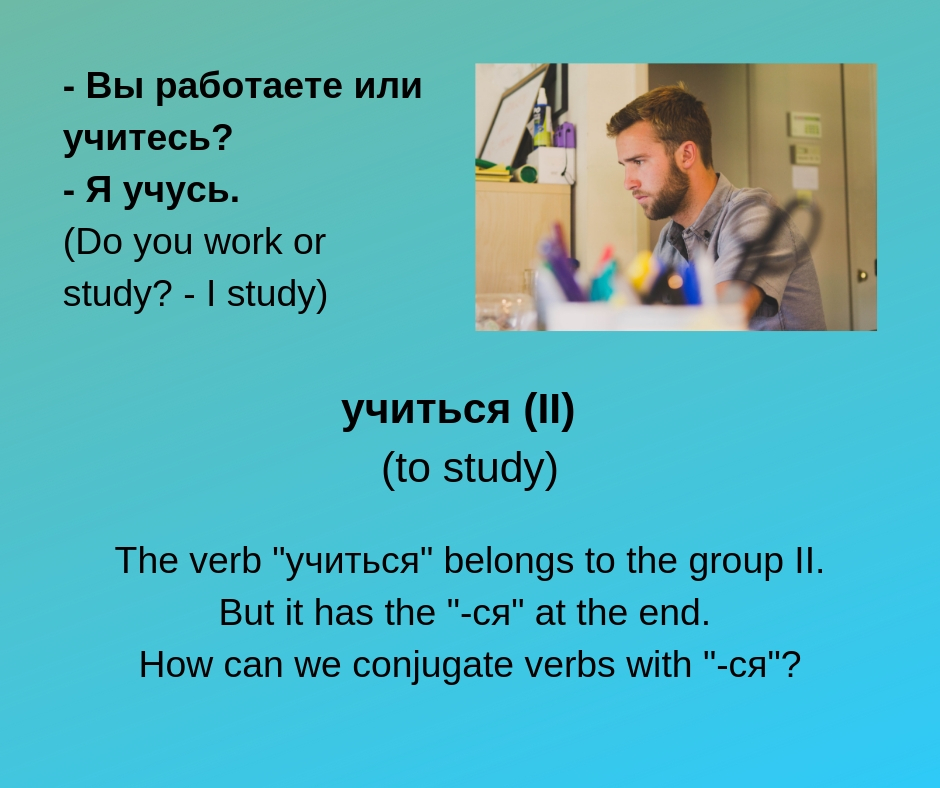

Verbs with “-ся”

Features of conjugation

\

- Вы работаете или учитесь?

– Я учусь.

(Do you work or study? – I study)

\

The verb “учиться” belongs to the group II, similar to “говорить”.

But it has a special feature – it’s “-ся” at the end.

How to conjugate verbs with “-ся”?

\

\

\

учиться (II)

(to study)

Я уч-у-сь

Ты уч-ишь-ся

Он (она) уч-ит-ся (“тся” is pronounced [ца])

\

Мы уч-им-ся

Вы уч-ите-сь

Они уч-ат-ся (“тся” is pronounced [ца])

\

1. The endings are the same as the “normal” group II endings

\

2. “-ся” goes AFTER an ending

\

3. Sometimes it’s “-ся”, and sometimes it’s “-сь”.

\

Question: What do you think the criterion to choose between “-ся” and “-сь” is?

\

\

Have you noticed the regularity?

The criterion is purely phonetical:

\

Consonant + СЯ

Vowel + СЬ

\

You can use this audio to memorize Present tense forms of the verb “учиться”. Pay attention to the pronunciation of “-тся” in “он” and “они” forms.

\

\

\

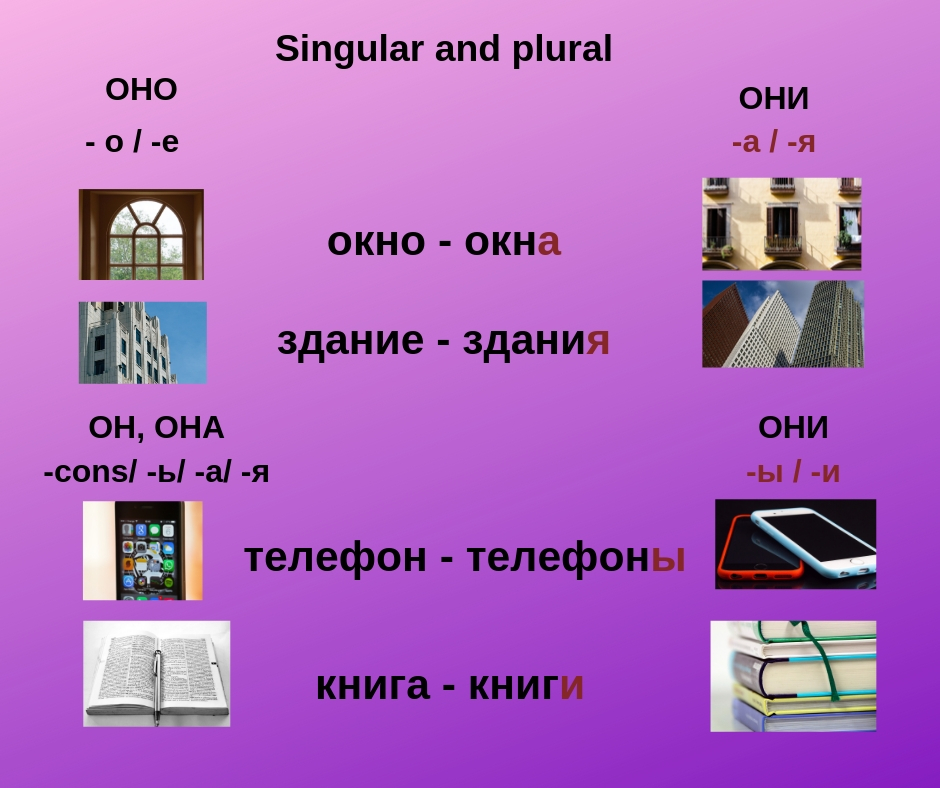

The plural form (Nominative).

\

- Что это?

- Это телефоны.

(What’s this? – These are phones).

\

окно – окна

(window – windows)

здание – здания

(building – buildings)

\

телефон – телефоны

(phone – phones)

\

книга – книги

(book – books)

\

You can see from the examples that there’re 4 different engings for Nominative plural in Russian: “-а”, “-я”, “-ы”, “-и”.

What nouns have “-а /-я” and what nouns have “-ы /-и” ending in plural?

\

\

\

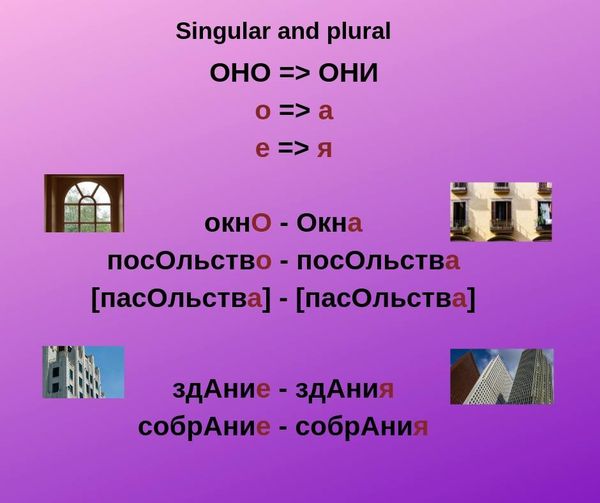

If a word ends in “-о” or “-е” in a dictionary form (neuter), it gets “-а” or “-я” in plural.

\

For example:

окно – окна

(window – windows)

\

письмо – письма

(letter – letters)

\

посольство – посольства

(embassy – embassies)

\

здание – здания

(building – buildings)

\

собрание – собрания

(meeting – meetings)

\

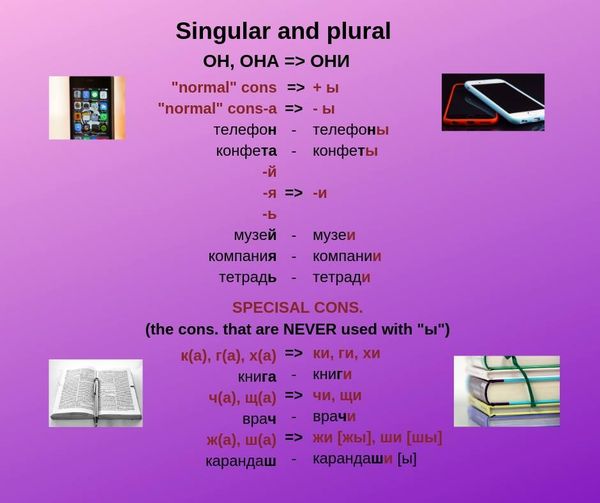

If a word ends in a cons. or “-ь”, “-а” or “-я” in a dictionary form (i e any masculine and feminine noun), its ending in plural is “-ы” or “-и”.

\

For example:

\

телефон – телефоны

(phone – phones)

\

торт – торты

(cake – cakes)

\

музей – музеи

(museum – museums)

\

тетрадь – тетради

(notebook – notebooks)

\

комната – комнаты

(room – rooms)

\

книга – книги

(book – books)

\

компания – компании

(company – companies)

\

The next questions are:

\

1. What neuter nouns have “-а” and what neuter nouns have “-я” in plural, – what’s the criterion?

\

2. What masculine/ feminine nouns have “-ы” and what masculine/ feminine nouns have “-и” in plural, – what are the criteria?

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

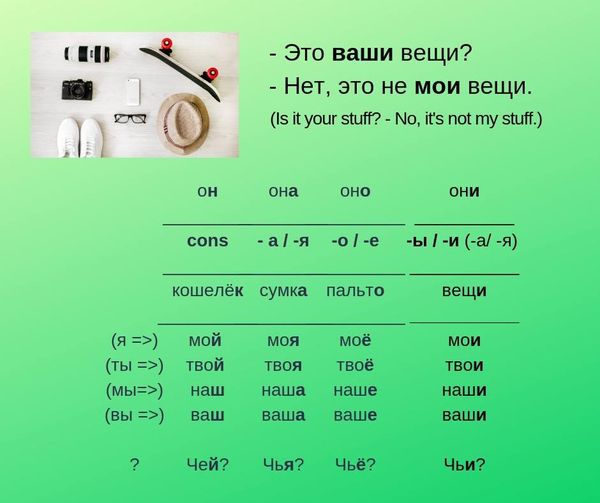

ЭТО ВАШИ ВЕЩИ?

The plural form of possessive pronouns.

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

Какое это кресло?

Adjectives (Nominative)

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\